O Canaan, beautiful Canaan,

it’s there I want to live forever

a place where milk and honey flows,

a place where sin will never go

it’s there I pray to always stay,

forever with Christ, my savior.

-Haitian gospel song (translated from Haitian Creole)

Act I: Genesis

As they arrive at church that Saturday, the crowd appears to number in the hundreds, maybe more. A man stands before them on stage. He leans forward to speak into a microphone as hundreds of hands wave in the air.

“We’re going to war!” he shouts. We’re going to war! the crowd shouts back, some clenching their fists, others open-palmed, as if calling on God for support. “We’re going to fight back!” the man calls out. We’re going to fight back! the crowd responds. A cell phone video taken at the event shows hundreds of hands reach down to the ground to pick up rocks and rubble, which they grip and lift high above their heads.

Swiftly, purposefully, they march from the church to a city 16 kilometers away. As they walk, they smile, laugh, and dance to Christian music that blares from a truck loaded with speakers. March, march, march! the people sing.

It’s August 2023, and over the previous 13 years, residents had built the city from nothing. Wedged between the mountains, a mass grave site, and the sea, Canaan had never been a paradise. Haiti’s government never recognized it as its own municipality, never gave its residents titles to the land. But they had transformed what was once a no-man’s-land into a haven of relative peace and safety — for a time. Canaan’s very existence testified to Haitians’ remarkable ability to make do, in spite of the powers that be.

The assassination of Haiti’s president, in 2021, put their resolution to the test. Armed groups have since taken control of an estimated 80% of the country’s capital, Port-au-Prince. In January 2023, these gangs conquered large swaths of Canaan and neighboring Croix-des-Bouquets, killing dozens of people and kidnapping others for ransom. Gang members wielding semiautomatic weapons shot residents who had no money to give them, or for no reason at all. Canaan’s residents sheltered in churches or fled to the countryside or Port-au-Prince. Those who remained risked their lives every day to do so.

Refusing to sit by as armed groups laid waste to their creation, some now put their faith in the man at the microphone. He promised to help them reclaim their promised land. His name was Pastor Marcorel Zidor, and he was a man of miracles. At his church on Saturdays, he was known to heal the sick. When he told his flock their faith would shield them from the gang’s bullets, many believed him — or wanted to believe. Unlike Haiti’s government or its police, who rarely stepped foot inside Canaan and didn’t dare confront the gangs, Pastor Marco had never failed them before.

And so, Pastor Marco led them into battle. Some wore yellow-and-white T-shirts emblazoned with a cross and Pastor Marco’s name. As they marched, more and more people seemed to join along the way — men, women, boys in school uniforms, girls with beads in their hair, wearing their Sunday dress. They appeared to find power and joy in numbers, reassuring one another and chanting in unison: “May God give us strength.”

Though the police would later allege that some marchers carried guns, videos reveal that the vast majority didn’t. To confront the gangs without firearms or support from the police may sound foolhardy. But the tactic — bombarding gangs with nothing but their own bodies — had worked before. A few months earlier, vigilantes in the capital stoned suspected gang members to death in broad daylight. In the weeks that followed, 160 suspected gang members were killed in subsequent attacks. The uprisings became known as bwa kale, a term that conjured using a knife to peel bark off a tree. In this spirit Marco’s followers were determined to take Canaan back.

A video shows a throng of people blocking traffic, car horns blaring as thousands of bodies fill the street. Men on motorcycles ferry others through the crowd. When they pass a police station, they pause, as if to see what the cops will do. But the police don’t try to stop them — or help them — so they continue marching past.

At last, they reach the road that forms the border of Canaan. They cross it, walking up a steep and rocky street. “We’re on their turf now,” says a man in a cell phone video, referring to the gang. “They’re shooting to make us turn back. But we are not turning back.”

Some brandish sticks, some machetes. Others clench rocks and stones. But many hands are empty, carrying no weapons at all. They appear to believe that, as Pastor Marco promised, God would protect them. After all, no one else ever had — or would.

Canaan came from catastrophe. On January 12, 2010, a 7.0-magnitude earthquake centered near Port-au-Prince sent concrete crashing down onto the heads and bodies of hundreds of thousands of people, killing between 46,000 and 316,000 — a difference of 270,000 lives, whose fate the state, and the world, doesn’t know. Haitians often refer to the disaster by its date, Douz Janvye, January 12, the same way Americans invoke 9/11.

That afternoon, Elvige Edrice, then 33, was in her small home in the city of Croix-des-Bouquets, adjacent to Port-au-Prince, listening to an evangelical radio program. The presenter was telling the biblical story of Jonah and the whale when the radio fell to the floor. “The house started to shake; there was so much noise,” Elvige told me in December 2019. “The house above us fell down. I felt like I was getting buried into the ground. People were yelling, ‘Where is my kid, where is my kid?’”

Earthquakes are not simply natural disasters. The severity of their destruction is a function of human activity, wealth, politics, and governance — whether people have enough money to build safely, and whether governments have the means to stop those who don’t. Four months later, an even stronger seismic event struck along the California–Baja border but injured only 233 people and killed just four. In 2018, a similar magnitude earthquake struck near Anchorage, Alaska; everyone survived.

To Elvige and some of her neighbors, Haiti’s earthquake went beyond man or nature. It was an act of God. Their pastors had warned them this day would come: rapture, the second coming of Christ, which would bring about the end of humanity. What else could explain the bodies and the blood, the rubble strewn everywhere? When she saw water bubbling up from the ground, the result of a broken water main, it reminded her of the biblical flood that destroyed the whole earth. But in Haiti, there was no Noah’s Ark.

“We saw the water and thought it might rise even more,” Elvige recalled. “We thought that the next day we would have a tsunami. People were saying, ‘The water will come — we must go to the promised land!’ So we all ran for the hills.”

They were joined by neighbors who carried food, tarps, and other supplies up toward the mountains north of Port-au-Prince, which extend to an area called Titanyen. Historically a dumping ground for the bodies of those who fell out of favor with the government, Titanyen soon became a mass grave site for those killed in the earthquake and, later, by a cholera epidemic. But in post-earthquake Haiti, space was in short supply. A place for the dead became home to the living.

Whether by coincidence or fate, the rocky terrain where Elvige’s group passed their first night was called Canaan, after the biblical promised land. Some say the name originated years earlier, when church groups visited the empty land to pray, but the name took on new significance after the earthquake. In the Book of Genesis, Canaan was the land of milk and honey that God promised to Abraham and his descendants thousands of years ago.

“This is the land on which we’re sitting now,” Elvige told me at our first meeting in May 2016. She gestured around her small plot, fenced in by thorny, cactus-like bushes she had planted to mark the space as her own.

My introduction to Canaan had come six years earlier, in November 2010. Back then it comprised a few thousand people living in tents on a barren hillside. I had trekked from the capital to report a story for the Associated Press. A tropical storm was bearing down upon the island, and my assignment was to learn how the settlers would weather it.

Haiti’s government and international NGOs sent dozens of school buses to Canaan to evacuate the settlers to higher ground. To my surprise, they refused to leave. Accustomed to their government’s tricks and empty promises, the settlers didn’t believe the buses would ever bring them back. They feared it was a ruse to clear them out, destroy their shelters, and evict them for good. The storm blew further south, sparing their settlement, and although their tents flooded, nobody died. The settlers’ refusal to flee a possible hurricane showed how little faith they had in their government — an ambivalence that would come to define Canaan as it grew.

Perhaps the only useful thing Haiti’s government did for the residents of Canaan was open the land to settlement. Two months after the earthquake, Haiti’s president declared the land public, which many took to mean free. Lured by the chance to finally have a piece of land to call their own and stymied by the government’s failure to provide them anywhere else to go, Haitians flocked to Canaan by the thousands.

Most had been forced out of the tent cities of Port-au-Prince, which popped up on scraps of private land and in public plazas after the quake. Without a comprehensive plan to resettle the 1.5 million people who’d been displaced, mere months after the disaster, the government began sending police — landlords sent thugs — to violently evict the displaced, destroying their tarps and tents and scattering their belongings.

Not everyone who came to Canaan had lost their homes to the quake. In the economic collapse that followed the physical one, some survivors struggled to pay their rent. They hoped Canaan would provide them a chance to escape and begin their lives anew. By 2015, an estimated 250,000 people called Canaan home. It had risen from nothing to become the size of Buffalo, New York; Madison, Wisconsin; or Irvine, California — and it was still growing. But there was a major difference between Canaan and these major American cities: The settlers of one of the world’s newest cities had to find a way to survive without any government at all.

Life in Canaan’s early days reminded me of the popular board game The Settlers of Catan. A settler of Canaan might spend the day creating a settlement, which consisted of laying a stone or concrete-block foundation around a plot of land to claim it as their own. They might build a rudimentary road, using picks and shovels to perform backbreaking work under the hot sun. In the hills, men with machetes rode horseback in search of tall grass for their cattle to eat — the cowboys of Canaan.

Those with green thumbs became farmers. They grew not wheat or sugarcane, but fruit, tubers, and tree nuts. Salma Simeus was among the cultivateurs. He and his wife planted moringa trees and harvested their seeds, which they ground into a peanut butter–like paste to sell to tourists and missionaries.

Others swung sledgehammers over and over to smash boulders into pebbles (and eventually sand) to mix with cement to build houses. Some dug drainage ditches so their homes wouldn’t flood when it rained. Planning committees set aside space for parks, schools, and hospitals, which they hoped Haiti’s government would someday build.

Day by day, the hardscrabble tent-scape looked more like a ramshackle city. Over its first three years, settlers invested an incredible $90 million of their own money into Canaan. The residents were not rich — the sum averages to about $300 per person, if Haiti’s government’s rough estimate that 300,000 people living there was correct — but they poured into Canaan every gourde they had. By 2016, they had built thousands of houses and dozens of churches and schools. Many neighborhoods had wells for water, and some had electricity. There were soccer fields and market squares, barber shops and one-room restaurants, tiny bars that blared Haitian compas music into the night until the power cut out.

“It’s extraordinary that it took less than six years for all these people to come here,” Salma told me one Sunday in May 2016 outside a church near his home. “Extraordinary.”

That morning we had followed the strains of a church choir and the sounds of frolicking children to a small compound, where I met Pastor Marc Loumette, who had founded a church and school in Salma’s neighborhood of Onaville in Canaan’s far east side. Clean-shaven and wearing a black suit despite the heat, he said he was planning a field trip to bring students to Haiti’s National Museum and the presidential palace in Port-au-Prince.

“It’s not enough for them to read in books. It’s important for them to learn about the history of our country,” Pastor Loumette said. “The history of our palace, the history of our state.” In 2010, Loumette had put his money where his mouth was, investing $2,300 of his own, donated, and loaned funds to build his church and school.

“Why go through so much trouble and expense to live here?” I asked. In reply, he recited Exodus 14, his favorite biblical passage. As Moses led the Israelites from captivity toward Canaan, they looked back with dismay to see their Egyptian masters pursuing them. They cried out to Moses, asking why he’d brought them to the desert to die. Moses said the Lord would fight for them if only they would stand still. Then the seas that Moses had parted for the Israelites returned and drowned the Egyptians.

“It’s like us,” the pastor said. “We don’t have water, we don’t have electricity. But for us to stay here on this land, we can’t be scared. We must have faith that God will help us.”

What God couldn’t do, the settlers tried to handle on their own. One hot Sunday I followed six members of a men’s church group — still wearing their polished black dress shoes, and without having loosened their ties or buttons — on a brisk walk under the blistering midday sun. They walked swiftly, in single file. One man carried a bible. Fifteen minutes later, soaked in sweat, we arrived at a house with brick walls and a tin roof. Beaming with pride, the owner showed me inside the single-room structure and explained it was built entirely by volunteers from the church. “This is the first time I’ve had a house of my own,” he said.

In the early days, there were so few settlers that “we all knew each other,” Elvige said in December 2018. “Someone would make food and we would all eat that food together. People wouldn’t get mad at one another — they were all in the same situation.”

But not everyone progressed equally. When some of Elvige’s neighbors organized to buy electrical cables to wire their neighborhood to the public grid, she watched men attach ropes to wooden poles, line up ten deep as though starting a game of tug-of-war, and then pull with all their strength, guiding the poles toward the sky. Later, men shimmied up the poles to connect cables they’d purchased, which they connected to a transformer on the public grid. To buy the poles and cables, “everybody paid 5,000 gourdes to a committee,” Elvige explained — about $114. “But I didn’t have the money.” She was literally left in the dark, her two children forced to do their homework by kerosene or candlelight.

With no mayor, police officers, or judges to turn to when disputes arose, people looked to informal neighborhood leaders — men, usually — who were considered trustworthy enough to arbitrate. Salma, the gardener, was among them. Hardly a minute went by that he didn’t receive a call on one or both of his cell phones from residents pleading with him to resolve a dispute, secure funding for a construction project, or find them a job.

One afternoon a scowling, hungover man in his 20s stopped us on the street. He was a former drug dealer and an all-around troublemaker, Salma later told me. He wanted Salma to help him make peace with his mother so he could move back in with her after months on the run.

Salma reminded him why she kicked him out in the first place: “Your mom bought you a motorcycle, and you sold it.”

“It was stolen,” the guy said, unconvincingly.

“You say it was stolen; she says you stole it,” Salma replied.

The man said nothing, silently pleading for Salma to intervene.

“M’ap vini,” Salma relented. “I’ll come by.” He managed to smooth things over, and the man moved back into the house. But a year or so later, a gangster named Little Tuesday shot him dead. Over what business, Salma didn’t know.

As the city grew, the disagreements became too fierce, and the stakeholders too many, for any one person to resolve. By that time the American Red Cross had come around with money to spend. Within hours of the 2010 earthquake, the charity had solicited donations for emergency relief. Tens of millions of Americans responded, sending the Red Cross an unprecedented half a billion dollars — far more than it knew what to do with. Initially, the charity promised to build houses for the displaced, but it later shifted its priorities to provide construction materials and training for Haitians to build homes themselves.

Enter Canaan. Starting in 2010, just months after the quake, the Red Cross made a push “to identify reliable local leaders who could act as an interface between the local population and external institutions,” according to a study by independent researchers. The charity identified nine distinct neighborhoods, and nine committees emerged. Residents could attend committee meetings to listen, offer input, and, when it came to disagreements, make their case. Committees spent hours arbitrating personal disputes or debating where a home, school, church, or park should be built, until some sort of consensus was reached.

The study found that although this system had no legal status, “in this political void, the neighborhood (committees) played a key role” in approving the NGO’s projects: “The fact that Canaanites, who were neglected for so long, have received attention and been ‘put on the map’ has given them hope for brighter days.”

Self-governance was not always rosy. No authority had a monopoly on force or power, or the final say on land ownership. Canaan had no police to keep the peace and instill relative order. Its nine neighborhood committees had no official mandate or formal authority, and no ability to enforce their decisions.

Elvige, who served on one committee, discovered the perils of politics in 2016, when international donors teamed up with Haitian government planners to build Canaan’s first paved road, a public transportation hub, and a food market just a stone’s throw from her home. The market would bring commerce and employment for ti machann — small-time sellers like Elvige, who had been peddling used clothes and hygiene products. Elvige hoped to open a stall at the market and use her earnings to pay her two sons’ school fees so she wouldn’t have to educate them at home. But not everyone was on board. Among the opponents was a man some residents referred to as Alia, who owned a handful of houses that would have to be demolished to make way for the project. The NGOs offered compensation for his loss, but Alia refused.

Elvige attempted to persuade Alia and his friends that the project would benefit the whole community. “I tried to talk to those people,” she said. “I told them: This zone needs to develop!”

But Alia, who was known to walk around with a pistol on his belt, did not agree. He accused Elvige of trying to steal his land from underneath him and sell it to the NGOs. Elvige says he became so enraged that he ordered a hit on her. (A staffer at an NGO that backed the project corroborated the accusation.) Frightened, Elvige called the father of her younger child, who knew the man. “What are your plans for your kid?” she asked. “Because I am going to be killed!”

Fortunately, her ex called Alia, who then summoned Elvige to talk. He told her he’d already paid the hit man to kill her, so if she wanted to live, she’d have to pay back the bounty on her head. Elvige saw no option but to sell the small chicken coop she’d been building. Alia also demanded that she resign from the neighborhood committee. Elvige couldn’t risk orphaning her children. She complied.

Together, the loss of the market project, death threat, extortion, and end of her committee post were catastrophic for Elvige. She couldn’t earn enough money to pay her children’s school fees. Instead of accessing a thriving marketplace and growing her business, Elvige spent her days in her cactus-covered yard, teaching French and math to her sons on a makeshift chalkboard.

I asked Elvige why she stayed in a place where she could so easily be killed.

“If the government of Haiti would come,” Elvige told me, “I would love for my children to live here forever.”

Act II: Kings

One spring night, on a drive from Canaan to Port-au-Prince, I watched the headlights of buses and trucks illuminating dust on the road. Soon it was pouring. Humidity, heat, and exhaust wafted in through the windows and the vents of our car. Children returning home from school in uniforms and little backpacks tiptoed down the middle of the road, where the ground was higher, weaving through the mess of traffic. Some held tiny plastic bags above their heads, as if to fool the rain.

Suddenly our car came upon a clearing. “What’s that?” I asked the driver, surprised by all the space. “A swimming pool,” he said in a deadpan tone. The water was so deep that other cars were avoiding it altogether. Grown men and women held hands as they took the plunge to traverse the dark water. One wrong step and the water might have been up to their necks. Even so, some couldn’t help but smile and laugh at the absurdity of it all.

We weren’t in Canaan, where drainage viaducts simply hadn’t been built. This was Port-au-Prince, the capital city — centuries old and still lacking sewers. That night, the nine-mile drive to Haiti’s capital took longer than my 700-mile flight from Miami. The settlers often seemed to yearn for a “state” or “government” — district offices, municipal leaders, a city hall — as though it would be panacea for Canaan’s growing pains. When the state finally arrived in Canaan, the thinking seemed to be, so would paved roads, electricity, and water infrastructure, as well as schools and courts.

But driving through the swimming pool, I wondered, How could they expect the state to show up in Canaan if it had barely done so in Port-au-Prince?

Haiti’s national government was like a distant dream for the settlers. Nearly everyone I spoke with told me the government simply did not exist in Canaan. “I haven’t seen the presence of the state,” Elvige told me in December 2018. Haiti’s president “has never stepped foot here. Maybe he passed over in a helicopter,” she joked.

To many Haitians, the settlers’ uncertainty over whether the government would provide any aid wouldn’t sound unusual or even new. Canaan was the product of two centuries of tension within the republic. In Haiti: State Against Nation, Haitian anthropologist Michel-Rolph Trouillot describes the country as defined by an eternal conflict between the government and the people. In Haiti’s Predatory Republic, political scientist Robert Fatton writes that it has enjoyed few, if any, periods in which the social contract between people and their government has functioned. The situation dates to Haiti’s earliest days.

Like the Israelites who fled slavery in search of their Canaan, Haiti’s founders were born as slaves but died free. Some were maroons who had escaped slavery and lived clandestinely in the hills and hard-to-reach tips of the island. In 1791, the slaves rose up against their French masters. After 13 years of fighting, they founded the world’s first and only nation of rebelled slaves.

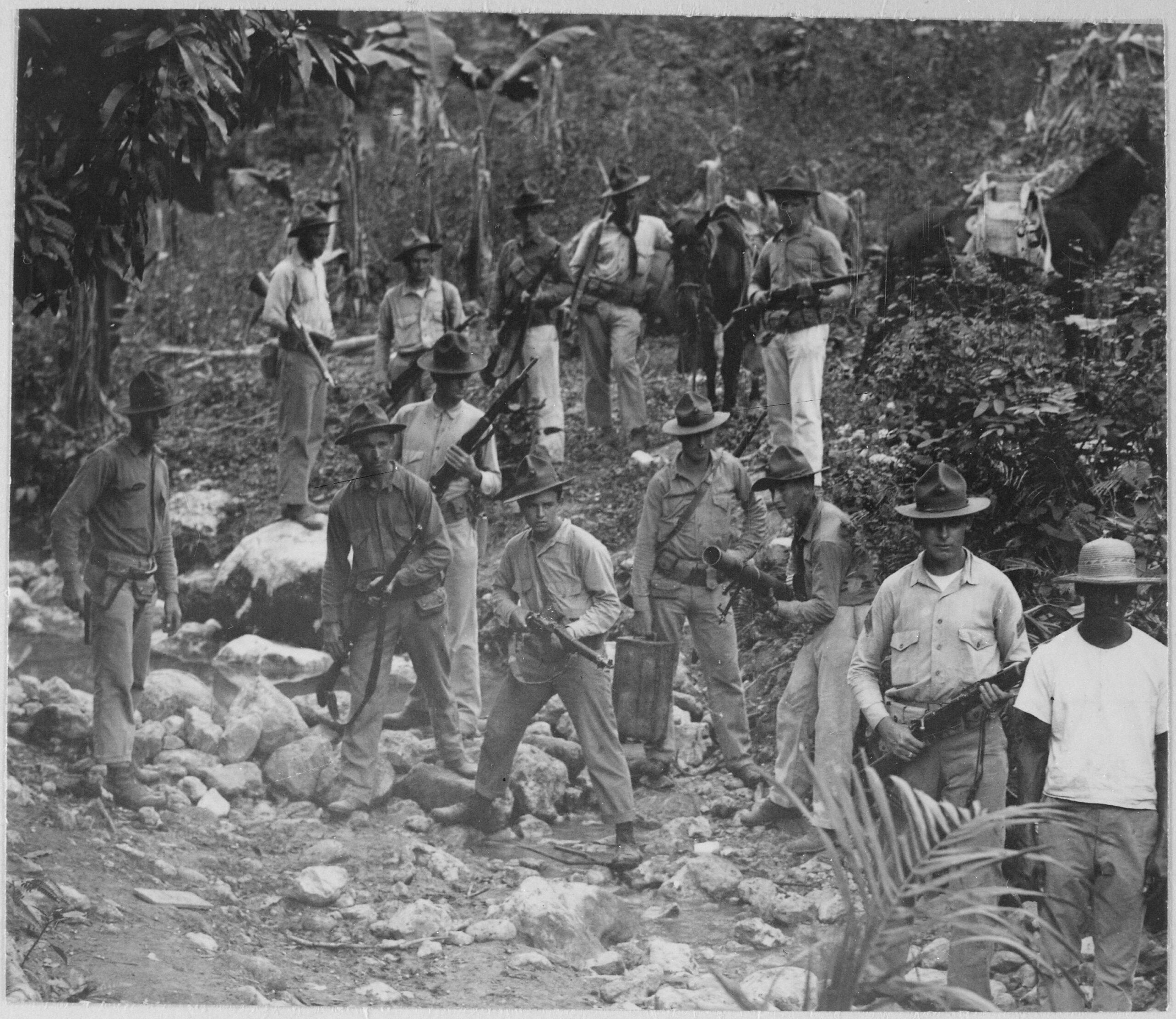

But their freedom was never absolute. At times it was barely more than freedom from slavery. But Haitians have been defending it ever since — from predatory leaders, blockades by foreign naval ships, and the U.S. Marines, who invaded Haiti in 1915 and brutally occupied it for nearly 20 years.

Throughout, Haitians found ways to resist state power.

Chief among them was marronage, a strategy of evasion. In the republic’s early years, Haitians fled from plantations to the forested mountains, where they practiced subsistence agriculture on tiny, rocky plots, writes the historian Johnhenry Gonzalez in his book Maroon Nation. Unlike sugarcane, which had to be processed and sold, the root vegetables and tubers they planted were hard for a visiting official to see, let alone tax. Many Haitians bartered to avoid the cash economy altogether, Gonzales writes. Others sold coffee, rice, and wares at secret marketplaces where the state couldn’t tax them. Meanwhile, “contraband goods” from abroad were “smuggled in at any point along Haiti’s long, rugged coast.”

But “the lawlessness of the maroon nation was a double-edged sword,” Gonzales writes. If poor, rural Haitians could avoid taxes, wealthy urban ones could, too. And they did. Throughout its first century, Haiti’s coffers, already strained by the odious debt it was forced to pay France for its independence, were empty. The American occupation of 1915 to 1934, predicated on protecting American investments, further consolidated power in Port-au-Prince. By the 1970s, Trouillot writes, Haitian rulers and foreign “experts” had written off the rural poor — with dire consequences: “The already huge gap between the haves and the have-nots widened at frightening speed. Inflation and corruption grew as well.”

Anthropologist Vincent Joos describes another Haitian strategy for avoiding the state: the lakou system. The lakou stands for a centuries-old practice of communal self-help in which Haitians clustered their homes around a communal courtyard and worked together to process crops, socialize, and build cohesion. “This system thrives on people’s trust, reciprocity, and solidarity,” Joos writes, and “enabled a majority of Haitians to live autonomously, mostly away from the state.” Over the rapid urbanization of the past 50 years, rural migrants brought to Port-au-Prince “values of the lakou.”

Today these values of self-help are embedded into the fabric of Canaan. Residents team up to construct houses, erect power lines, and debate where to establish schools, roads, and businesses. But Canaan also reveals harsh limits to what people living outside the state can achieve.

Not all of Haiti’s bureaucrats, in their air-conditioned offices in Port-au-Prince, liked the direction in which Canaan was heading. Construction was “anarchic.” Neighborhoods operated independently. Even though it was one of Haiti’s largest cities, it had no center.

“Seeing Canaan as a problem to be corrected, the state’s response has been top-down,” writes a team of researchers who studied Canaan. But this assertion contrasted with the residents’ reality: For six years they’d been building their city from the bottom up.

“The worst-case scenario is that the central government and local governments never invest in Canaan — in infrastructure,” said Clement Belizaire, who headed Haiti’s post-earthquake reconstruction bureau. On one of my visits in 2016, Belizaire’s agency was installing 100 small concrete markers throughout the city to delineate where future roads should be built and to keep residents from encroaching upon them. But upper-level bureaucrats regularly commandeered government vehicles for their own personal use, leaving their employees without the means to travel to Canaan and do their jobs. International NGOs resorted to sending gas money to the rank and file so they could drive out in their own cars to rubber-stamp the charities’ projects.

Six years after the earthquake, Haiti’s leaders had done little for the residents of Canaan.

“When we say the Haitian government is a failed state or nonexistent, the fact that they’re nonexistent is a choice,” said an American aid specialist with years of experience in Haiti, including in Canaan, who was not authorized to speak on the record for fear of backlash by her organization’s government partners. “Yes, they don’t have a lot of funds, but they make an explicit choice as to where their funds go. They have agency. But they’re not choosing to invest it in Canaan.”

To fill the void where they believed an official government should have been, Canaan’s residents needed someone on the ground. Someone with resolve, with money — with power. They turned to a man who wanted Canaan for himself: the mayor of the city next door.

I got my first glimpse of Rony Colin, the mayor of the abutting Croix-des-Bouquets, in December 2018. It was a momentous occasion, as he was inaugurating Canaan’s first police station. It was a Tuesday, but several dozen settlers showed up in their Sunday best. Rony arrived late and sauntered to the police post, holding his chin up and wearing his slight signature frown.

A round man just shy of average height, he was wearing blue pants and a blazer with a small pin of Haiti’s blue-and-red flag. Seeming to grow fatigued as he watched workers dig light posts for the station, Rony leaned against a concrete wall, his blazer gathering dust, and picked dirt from under his nails. Uniformed police escorts stood beside him, semiautomatic weapons at their side.

“We’ll do it quick,” Rony said, describing half a dozen new police stations he claimed would soon dot Canaan. “We’re going to put officers in every one.”

Those in attendance included Evenson Louis, wearing a white button-down, gray dress pants, and a satisfied smile. In the earlier years of the city, Evenson and his neighbors had preserved a small plot of land for a future police station. Now, one such station had finally come. A police presence was crucial to maintaining harmony, Evenson felt. Citizens could set aside space for parks, schools, and hospitals, as he and his neighbors had; they could even put their heads and funds together and erect them. But mere civilians couldn’t enforce their decisions or fight crime. They needed police to protect women like Elvige from death threats and extortion, and to hold wrongdoers to account.

Evenson’s hilltop neighborhood was one of the best planned and least dense in the area, and Evenson, one of its earliest residents, described it with pride. “It’s a different style of life. We’re no longer a tent camp. We are like the bourgeoisie,” he said. Gazing down the mountain toward Port-au-Prince, he added, “We don’t want to live like those people down there. We don’t live like in Somalia. People feel at ease.”

Evenson and I watched Rony pose for photos in front of the station. The smell of burning trash wafted in with the breeze. Someone had set fire to a mound of garbage that Rony’s municipal workers from Croix-des-Bouquets hadn’t bothered to collect.

Three municipalities shared the land on which Canaan rests, and each tried to exert their power over Canaan. Municipal workers walked the city’s dirt paths and alleyways demanding bribes from people who hadn’t obtained construction permits to build their businesses or homes. Sometimes they seized construction materials, like cement and iron, when people refused to pay the bribes. But as mayor of a nearby city with a legitimate claim to part of the territory that formed Canaan, Rony could do things the settlers could not: sign off on roads, schools, and marketplaces — and sign the eviction notices of people who had to be moved to create them.

Earlier that year, in July 2018, the American Red Cross, along with the U.S. Agency for International Development and the International Organization for Migration, completed Canaan’s first paved road. It was modest, just one lane in each direction, and spanned only one-and-a-half miles. Still, it passed straight through the city’s center, connecting to the national highway that leads to Port-au-Prince and beyond. Instead of directing the road through what urban planners deemed the “rational” path, engineers more or less traced the existing path that residents had created, so as to avoid too many of the forced evictions with which Haitians are all too familiar.

Mayor Rony had signed off on the road and inaugurated it once it was complete, but in subsequent conversations, he claimed to be a reluctant politician. Whenever I asked him about Canaan, he spoke mostly about his business interests. I got the impression he was less concerned with the complex task of governing Canaan than with profiting from the place — and not just through potential tax revenues.

Rony owned a construction company as well as the sand mines in Canaan’s northern mountains. He had even opened a radio station on which commentators whispered political opinions into their fellow citizens’ ears. The police station, too, seemed at least somewhat self-serving, as it would help Rony expand his control.

The day after inaugurating the station, Rony invited the leaders of Canaan’s nine neighborhood committees — about 30 people — to his home. They gathered in his compound, gossiping about which international NGOs had left and which ones remained, which had money for projects and which didn’t. Salma was among them, and when someone asked whether the Red Cross was ever coming back, he said he didn’t know — he had been busy trying to find work with Oxfam.

Waiting outside his house for the meeting to start, the mayor’s deputy, Geraldine Cetoute, tried to tamp down expectations, telling me the settlers’ concerns were “problems of the central government.” Canaan was “becoming slumified,” she said, with anarchic construction, tax shirking, and the general poverty of the residents. Given the low crime rate at the time and the fact that residents had invested to the tune of $90 million, I was skeptical.

At last, the community leaders were ushered inside a modest room. Mayor Rony, who had traded his suit for a T-shirt, handed a 1,000 gourde note — about $13 — to a soda vendor, who reached into his cooler and passed around Cokes.

Mayor Rony congratulated the leaders for being there, for “entering the state.” “I’ve built a name for myself,” he boasted. “People call this ‘Rony-Colin-Ville.’” The upshot of his oration was that if the community leaders trusted and supported him, no one would face injustice on his watch. Instead, he’d be their protector.

Salma, sitting next to me, scribbled notes. I couldn’t read his expression. More than most, Salma knew what Haitian politics look like up close. Since 2006 he had worked as a parliamentary police officer, where he’d seen politicians bicker over bills and engage in fistfights over funding. The irony was sharp: Salma earned his living protecting the government that barely governed, or protected, residents like him.

He spoke of these matters in the hours we spent together, walking his goats around his neighborhood, Onaville, as they nibbled shrubs; watching soccer practice at the academy across the road; or sitting in plastic chairs under the shade of his moringa trees. In Haiti, power doesn’t grow on trees. The only way to obtain it, Salma told me, was to mete tèt ansanm — put your heads together and take it.

Beneath Salma’s sleepy demeanor lay serious misgivings about Rony’s rule. Rather than reveal them directly, Salma posed a question to Rony, a subtle test of whether the mayor would be willing to take responsibility for solving the city’s problems or merely deflect.

“Onaville has a ravine problem,” Salma began. The neighborhood was cut by a ravine that overflowed and caused major floods in the rainy season. In Haiti, there’s a Creole proverb: Kay koule twompe soley men li pa twompe lapli — a leaky house can fool the sun, but it cannot fool the rain. When heavy clouds roll over Canaan and unleash their payload, water pours through settlers’ rooftops and walls, drenching them and everything they own. Dirt floors become mud.

But when Salma brought up the problem, Rony failed the test: He deflected, pointing a finger back at the residents. What had prevented Canaan from advancing and its people from becoming full-fledged citizens, he argued, was their failure to take responsibility.

“Ravine is a problem,” Rony replied. “But I can’t do anything about it if people don’t pay their tax.”

One year after the meeting, I was sitting in the back of Rony’s SUV as it bounced down a bumpy road — one of many unmaintained passageways under the mayor’s jurisdiction. “Economic advancement is what I want,” he told me. “For the state to bring electricity, for the state to bring water, for the state to bring roads. But they can’t bring that without money.” And to collect money, a government must tax.

“Everybody talks about Delmas,” Mayor Rony said, referencing a working-class district in Port-au-Prince where I lived. “People pay tax, and then that money is put into projects.”

After the earthquake, I had reported on USAID and discovered the agency wasted hundreds of millions of dollars of so-called “aid.” But I also reported on a project that went right: USAID had funded a program to help the mayor of Delmas collect taxes, certify land and house ownership, and build roads. Over a five-year period, the rubble-filled alleyways of Delmas slowly morphed into smooth, paved streets.

But not everything went smoothly. When builders went unpaid for weeks, they blocked the road in protest. There were accusations that the Delmas mayor had siphoned off some of the money. “But now all those roads are paved!” Anna Konotchick, Canaan program manager for the American Red Cross, told me. “And the city has a tax base,” she added, “which was created by the USAID.”

In Canaan, every resident I spoke with professed a desire to pay taxes on their land and houses. To pay tax is to earn legitimacy, to assert a social contract that obligates the government to provide the services their new city lacks. Around the time of my conversation with Rony, the U.S. and Haitian governments, along with Habitat for Humanity, were working to formalize the settlers’ land tenure status in Canaan. They had surveyed some 20,000 households with the goal of providing title — and a base for property taxes.

But in February 2020, gangs launched a series of attacks on municipal offices in Croix-des-Bouquets. That December a young police officer was shot and killed. The project was put on hold, and Canaan never got a system for collecting tax on its own.

Sitting in his SUV, Mayor Rony described Canaan as a gamble. But for Canaan’s residents, Rony was a gamble, too. Deserved or not, his reputation was plagued by allegations of land grabbing and infighting. Normal fighting, too: Haiti’s oldest newspaper reported on a “war” between Mayor Rony and officials from neighboring Cabaret, another commune fighting for control over Canaan. According to the paper, an administrator from Cabaret said a colleague was beaten bloody, her left eye requiring stitches, by “armed bandits” positioned by Mayor Rony. In the same article, Mayor Rony denies the account, citing lawlessness in the area which, besides, was not under his purview.

As Canaan’s residents came to know Rony better, not all of them liked what they saw. Soon an entire neighborhood learned the danger of placing their futures in Rony’s hands.

It started when a stranger arrived in Evenson’s neighborhood from what Haitians call lòt bò dlo — the other side of the water, or America. Evenson called him “Miami.” He wanted to build a house next to the park that residents had preserved, as well as a grocery store the whole community could enjoy. Evenson visibly puffed out his chest at the thought: Someone had come all the way from America to live here, in his neighborhood — the neighborhood he had helped create. What’s more, Evenson had always dreamed of having a market, complete with all the business, money, and jobs it would bring.

But one morning Evenson awoke to discover that overnight, masons had erected a short stone wall around the park. Everyone knew what that meant, because they’d once done the same thing themselves: Miami was cordoning off the public space for his own private residence.

Within minutes, Evenson convened dozens of settlers to protest at the park, interrupting the work. A few days later they constructed two large concrete benches in the shade of a tree in the park’s center. The benches were a claim to the space, a defense. Now the plot looked more like a proper park. As insurance, Evenson persuaded a deputy from Croix-des-Bouquets to declare the land public property. A small billboard soon appeared in the park stating as much. “We were trying to find a way to resolve this,” Evenson told me. “We don’t want a war.”

A few days later, Miami was back, taking photos of the park. “We knew exactly what he was doing,” said Evenson, who followed him to Rony’s office. “They showed us this paper. It said, ‘The mayor recognizes Mr. so-and-so, who has a parcel of land.’” The paper didn’t specify the man’s name or the location of the land, but the implication was clear: The mayor’s office had given him the go-ahead to build. No matter that a deputy from the same office had already declared the land public. “It was a forgery,” Evenson said of this new document. “We didn’t want to believe it. We were so mad.”

Soon after, police officers detained Evenson as he was leaving a meeting and brought him to the nearby station where he was questioned by the police commissioner regarding the land conflict with Miami. “A complaint is filed against you. You are preventing the development of the community,” the commissioner accused him. “Take him to prison.”

Evenson spent the night in a cell in Mayor Rony’s jurisdiction of Croix-des-Bouquets.

The next morning, fellow settlers descended on the jail, demanding Evenson’s release. A judge questioned Evenson briefly before ruling that the police didn’t have the right to arrest him for defending a public place. Outside, Evenson thanked his fellow settlers for demonstrating in his defense. Just like the motto on Haiti’s national flag had promised, unity made strength. By rallying together to protect a rocky but sacrosanct space, the settlers had won. The grocery store was never built, and they never saw Miami again.

But in Canaan, such victories were few and far between. For many settlers, a decade after the earthquake daily life had become stagnant. It seemed as though all the opportunities and possibilities they had strived for had been a dream.

Act III: Lamentations

One morning in December 2019, as I walked through Canaan with Louis Jadotte, a Haitian consultant and project manager for UN-Habitat in the city, we came upon three kids hanging around a broken-down bus on a rocky side street. Per the signage on the bus, it had once served commuters in Dutchess County, New York, home to the town of Poughkeepsie. It later served commuters in Canaan. In its dusty afterlife, the bus had become a children’s playground.

A boy named Jonel sat in the driver’s seat, turning the steering wheel back and forth. He wore a black T-shirt featuring Yoda and Darth Vader and claimed to be 14, but he looked about 9.

Jadotte asked Jonel where the broken-down bus was headed. The boy replied it was going to the city of Gonaïves and invited us to pay our fare. Sensing further opportunity, he confided he’d be willing to sell us the bus for the reasonable sum of $50,000.

“What will you do with the money?” Jadotte asked.

“Pay my school fees,” Jonel replied.

Jonel explained that his father sold blue jeans on the street and his mother didn’t have any work. They had moved to Canaan the previous year because life and land were cheaper. “People can walk. There’s no shootings,” he told me when I asked what he liked about Canaan. “Here I have more freedom.”

As we bantered, Jonel’s older brother boarded the bus carrying a small gray device that resembled an oversize calculator. It was a lottery machine, ubiquitous in Haiti, that doled out tickets with any two-digit number you wanted for any wager you were able to pay. Twice a day, winning numbers were announced on national TV and radio stations across the country.

Jonel grabbed the device and told us to pick a number, to place a bet.

“Fifty-five,” Jadotte replied, handing him 10 gourdes, about 10 cents at the time. Jonel punched a series of numbers into the device so quickly it looked like he was playing a video game. Jadotte inspected the ticket before handing it back to Jonel and telling him to cash it in if it won.

“If you’re a millionaire,” Jadotte told the boy, “then I’m a millionaire, too.”

As we left, I wondered what Jonel would do with such a windfall besides paying his school fees. Would he invest in Canaan? Would he try to stay there forever, no matter the cost, like Elvige planned to do? Or would he use the money to flee somewhere, anywhere, else?

But this choice would soon prove to be an illusion. Although we didn’t yet know it, Haiti’s already fragile state was about to be pushed over the edge. For Jonel and millions of other Haitians, there would be no escape.

The trouble had begun two years earlier, in 2017. Haiti’s senate — and later a state auditor — published reports alleging that prior to becoming president, Jovenel Moïse had helped pilfer part of nearly $2 billion in public funds, money Haiti was supposed to pay back to Venezuela for the oil that made its economy tick. The oil program was called PetroCaribe, and in Haiti the name became synonymous with scandal. (The senate report alleged the previous presidential administrations of Michel Martelly and René Préval had also been in on the graft.) When it became clear Haiti couldn’t pay its debts, Moïse cut fuel subsidies in 2018. Gas prices skyrocketed, inflation surged, and Haiti’s already fragile economy took a plunge.

Enraged at their leaders and struggling to feed their families, thousands of Haitians took to the streets to call for Moïse’s ouster in what became known as Peyi Lok, a strike that drove much of Port-au-Prince’s economy to a standstill. Police were overwhelmed. That December, an inspector in Canaan told me he had a couple officers under his command, “but we don’t have cars.”

“The state doesn’t take responsibility. The state isn’t here,” said the uniformed officer of the state.

Like their ancestors who used marronage tactics to defeat the French 200 years earlier, and the group that liberated Evenson Louis, Canaan residents banded together, barricading the entryways to the city using boulders and rocks. They stationed watchmen at the city’s entrances at night to keep the protests and politics out. They watched and waited to see whether Haiti’s president would be ousted from power. They wondered what would happen to their city as their country began to fracture.

Moïse’s administration responded to the protests with violence. In November 2018, senior officials met with a police officer, Jimmy Chérizier, who would become a notorious gang leader. Witnesses say they supplied him with the weapons that he and his cronies later used to massacre 71 people in the low-income neighborhood of La Saline. The following year, Chérizier’s gang killed 24 people in Bel-Air, another opposition neighborhood. Chérizier and other gang leaders went on to massacre 145 civilians, rape women, and burn homes in Cité Soleil. All three neighborhoods had turned out in large numbers to protest against Moïse.

Salma found himself on the front lines of the unrest. In September 2019 he was still commuting from Canaan each day to work as a security guard at Haiti’s Parliament when anticorruption protesters stormed the grounds to try and block the swearing in of a new prime minister. Salma watched, helpless, as they smashed windows and ransacked the place.

On September 23, a Haitian senator took out a gun and fired. A fragment struck my friend and former colleague, the Associated Press photographer Dieu-Nalio Chery. He had to be evacuated across the border to the Dominican Republic for surgery to remove a fragment lodged in his face. The shooting was caught on video, but the senator wasn’t charged. This sort of unrest and impunity was what Salma came to Canaan to escape.

When I visited the Parliament with Salma a few months after the riots, the place was eerily empty. Salma was still showing up for work each day in full uniform, but there was no longer any government to protect. Moïse had refused to organize new elections, and as 2019 drew to a close, so did the terms of Haiti’s last remaining legislators. Moïse was weeks away from ruling all of Haiti by decree. Haiti’s fragile democracy was ceasing to be.

“The president has gotten this country into a crisis,” Mayor Rony told me amid all the chaos. “When he starts ruling by decree, all that money, they can steal it,” he said of Moïse and his cronies. “These are people who start wars.”

By this time, Rony seldom spoke of Canaan unless prompted. He seemed far more interested in Haiti’s national politics, and some believed he might have his eyes on the presidency. Rony denied this to me, but his actions and grandiose speech hinted otherwise.

“Every citizen should be able to live here without persecution,” Rony said, a distillation of his vision for his constituents, his compatriots, and his nation.

But Rony’s tenure as mayor was running out. In January 2020, weeks after I visited the vacant Parliament building with Salma, Moïse began to rule by decree. Six months later, he took control of the nation’s 141 municipalities, giving himself the power to install any mayors he wished.

Moïse’s tenure, too, would be short-lived. In July 2021, he was dead — assassinated in his home at night by a gang of Colombian mercenaries hired by Haitian-American businessmen, a Haitian senator, and a former Chilean-Haitian drug dealer turned U.S. government informant. With no legislature, no elected president, and no elections in sight, Haiti had no democratically elected leaders left.

Things couldn’t get worse — but then they did. In the absence of the state, gangs had begun filling the void — kidnapping men, raping women and children, burning bodies (dead and alive) in the street. Police officers went unpaid, and some worked with the gangs or formed ones of their own. Kidnappings became so rife that after a decade spent reporting on Haiti, including two years living there, I could not safely return. In July 2021, the 400 Mawozo gang had established a stronghold on the outskirts of Canaan, stopping any vehicle that passed, extorting commuters, kidnapping them, and sometimes killing those who couldn’t pay.

A neurosurgeon turned politician named Ariel Henry — who Moïse had appointed to be acting prime minister just days before his death — became Haiti’s de facto leader, despite never having been confirmed to the post. Henry had the support of international powers like the United States, but never a mandate from the Haitian people.

In an attempt to find a way out of their nation’s political quagmire, Haitian civil society leaders and opposition politicians banded together on August 30, 2021, to sign the Montana Accord, named after a luxury hotel in the hills overlooking Port-au-Prince. In order to restart democracy and get their country back on track, it proposed a two-year interim government that would organize elections and give way to a permanent one. Signatories called on Henry to adopt it. He refused.

Then, that October, Henry called for the creation of an international military intervention to restore order and security to Haiti. But precedent didn’t bode well. A previous UN peacekeeping mission had indiscriminately slain civilians in the street, raped and sexually tortured men and boys, operated a child sex ring, and violated mission rules to exploit women and father hundreds of babies, leaving them behind without paying child support. It also started an ongoing cholera epidemic that has killed more than 10,000 people and sickened over 100,000 more. To this day, the UN has refused to compensate the victims.

The next month, Salma’s updates, sent via WhatsApp, were increasingly disconcerting. “It’s very ugly. We have water problems, electricity problems. We have so many difficulties,” he told me in a voice note. “The zone where I work has lots of banditry. Sometimes there’s dezod [chaos]. You can’t pass. The mayor does absolutely nothing,” he said of Rony. Salma hadn’t yet realized that the mayor had left — flown the coop to Florida a month earlier, after his young daughter was kidnapped and his mayoral term came to an end.

“If you come to Haiti now, you’ll see people dying from hunger because they can’t go out to the street,” Salma said. “But if they don’t go out to [find food], they’ll die at home.”

When I asked who should help Haiti get out of this mess, Salma pointed to a country that had played no small role in creating the chaos. “It’s arms from the U.S. that come here that are terrorizing people,” he said. It’s true: Journalists and prosecutors revealed that a former U.S. Marine was one of many Americans who had collectively been smuggling hundreds, if not thousands, of guns from America, the world’s largest arms exporter, into Haiti. “The police need reinforcement — we need any help we can get. Help us, Americans. Help us!”

By 2023, a brutal new gang — known by its leader, Jeff — began to infiltrate Canaan, shooting and killing people, kidnapping others, raping women and girls, and extorting people on the street.

To get help returning to their houses, a group of Canaanites went to the American embassy, Salma told me in an April 2023 message. “They want a military force, to reinforce the police.”

Instead, “the police tear-gassed them,” Salma said. “In your article, mention that.”

On August 12, 2023, I received another message from Salma. This one sounded hopeful. “We had a threat today in Onaville. Police shot eight bandits in a planned operation. We hope that this will improve things so people can return to their houses.”

Two weeks later, it’s that Saturday in August — the one where congregants went to church, then to war. Pastor Marco standing before a sea of people, their hands raised, clutching rubble. Polo shirts and machetes. Marco calling on them to march back into Canaan and chase out Jeff’s gang.

Cell phone videos capture what happens next. A crowd of protesters walks up a narrow, rocky street, pausing with trepidation, unsure what lays ahead. When the gang fires, people pause.

Then screams ring out.

People run.

One video shows a gang member with a semiautomatic weapon firing from a distance at anyone — men, women, children — who dared to dart across a road in an attempt to escape. Their bodies were left in the street. Two schoolchildren lay still, one piled on top of the other, as though they’d been running away together, their white shirts stained with blood. One girl’s eyes remained open, forcing the rest of us to remember the horror of the last thing she would ever see. Her mouth was open, compelling us to wonder what words she would never grow up to speak.

The gang took some settlers hostage and interrogated them. Some they released. Others were shown no such mercy. At least seven people died that day, and at least 10 more were shot. Gang members bound one man, covered him in gasoline, and burned him alive.

In the aftermath, prosecutors accused Pastor Marco of complicity in the killings, but Haiti’s justice system is in shambles and there’s no indication that the case against him has moved ahead. To this day he continues to preach.

None of the settlers I spoke to blamed Pastor Marco. They regret how it ended. But it wasn’t as though they had any other choice.

“He had made a lot of miracles, so he thought he could get rid of the bandits of Canaan,” Salma told me.

A few weeks after the massacre, gunmen attacked the nearest police station with a hail of bullets — a reminder, as if anybody needed one, of who is in charge.

On June 26, 2024, 400 police officers from the other side of the world — Kenya — touched down at Toussaint Louverture International Airport in Port-au-Prince. They were hired guns, mercenaries — approved by the UN and paid for by the U.S. — sent in a desperate attempt to somehow make things right.

Precedent doesn’t bode well. The same week they arrived, their colleagues back in Kenya were busy shooting at and killing scores of civilians — protesters demonstrating against Kenya’s president and a bill to drastically increase the nation’s already high tax. Having spent years living and reporting in both Kenya and Haiti, investigating extrajudicial killings by police and soldiers in the former and attending one of the July demonstrations in Nairobi in which two people were killed, I cannot fathom how such an intervention could turn out the way Haiti’s president and many of its people hope. “Another international force in Haiti will never work without a functional government in place,” the Haitian human rights defender Pierre Espérance wrote in the New York Times.

Four months earlier, in March 2024, Henry had traveled to Nairobi to meet Kenya’s president in an attempt to get the police officers deployed. By that time some of Haiti’s gangs had united and effectively finished taking over Port-au-Prince, including the area surrounding the airport. Henry was reportedly in the air when the U.S. State Department sent him a message instructing him to resign. A transitional council made up of Haitian politicians, diplomats, and urban planners installed a new prime minister and began the slow, difficult process of restarting Haitian democracy anew.

On June 8, Evenson sent me a series of voice messages. He sounded exhausted, desperate — not like the upbeat man who had the foresight to set aside land for a police station in Canaan’s early days. He spoke quickly, like he was running out of breath, like he had to get every word out before it was too late.

He said they don’t have much hope left for Canaan. “Whether the gangs treat you good or bad, you accept it,” he says, “because it’s been so long since the state has given us any hope.”

“These gangs are the children of the state,” he continued, explaining how the Haitian government created the gangs by arming them with guns sold to them by the police.

“I have a dream for this country to change,” he said. “I want this to be a good country for my kids, for my friends.” He dreamed aloud of a sister country helping rearrange and resurrect the state and “recognize that it’s us who can make this country good again.”

He hoped a new government would find a solution to Haiti’s interminable dysfunction and unrest: “We’re hoping for the best.”

Salma was forced to flee Canaan to live with relatives in Croix-des-Bouquets. “Today Canaan is a zone that nobody can pass,” he said.

Despite having no government left, Haitians both young and old remain immensely proud of their country. In June, Elvige sent me a video of her son giving a rousing speech, a poem, into a booming and echoing microphone at his school on Flag Day, which Haitians celebrate on May 18. Dramatic chords played in the background.

“My name is Céléstin Shneïder,” he began. “Every country has a flag.”

“Oh Haiti, country of Pétion, Henry Christophe,” he said, naming two of Haiti’s independence heroes. “Against mediocrity and catastrophe, they always remained tough.”

“The flag is the inspiration of my life. The flag is the destination of my country.”

“Our ancestors fought against slavery. My flag is the inspiration that gives me strength and courage.”

Elvige sent me a photo in which she is hugging her son at the ceremony, both of them wearing their Sunday best against a backdrop of white-and-pink curtains. Céléstin looks at the camera, defiant. Elvige gazes into the distance, pensive, her arms around him and her chin resting on his forehead. Hugging him as though for the last time.

“There is no future for us in Haiti,” Elvige wrote to me in June 2024. As if to ensure it, that month, the gang that controls Canaan burned down City Hall, the one Mayor Rony used to run, destroying the last physical vestige of a government that no longer exists. “There is no future for the boys. If I die, my children will be left in misery.”

“Everyone is trying to escape Canaan before the battle that will take place,” she said, referring to the arrival of the Kenyan police. “But us… we have nowhere to go.”